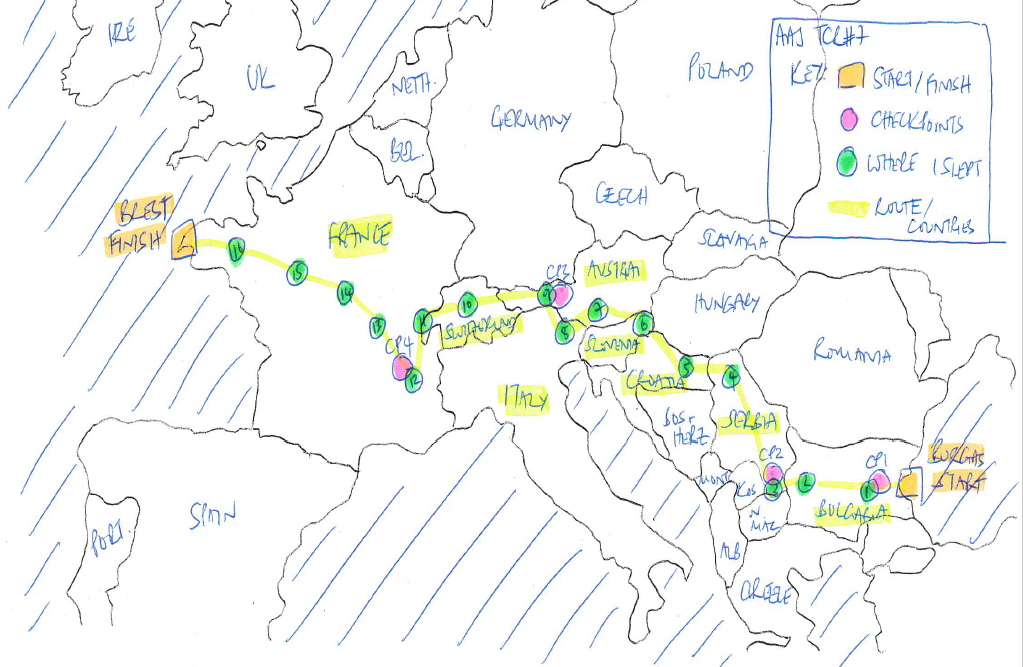

Amelia Ashton Jones, 44, a Programme Manager for the British Olympic Association, has competed in the Transcontinental race twice, in 2017 and in 2019. Here she gives a very thoughtful account her 2019 race, from Burgas on the Black Sea in Bulgaria to Brest, the most westerly tip of France, a journey which took her 16 days, 7 hours and 51 minutes*. She may make light of the race, but be in no doubt that cycling 4000 kilometres and climbing 40,000 metres is an immense achievement.

The Transcontinental, or TCR, is an ultra-distance bike-packing event held each summer in Europe. It crosses the continent, usually in a zig-zag pattern, via four checkpoint and mountain passes that change each year. The TCR is self-supported; competitors may buy food, equipment, mechanical repair and even hotel rooms along the way, but according to the rules it must be from commercial sources available to all riders. See more about the TCR.

* Race time per brevet card; time stamped at the finish in Brest. It is not official as it is just outside the 16 day General Classification cut off.

First a bit of Form

Amelia Ashton Jones: Sports and challenges are an integral part of my daily life. I cycle to work, I am a member of a local running club and regularly run the Wimbledon parkrun. Sport is also part of the day job, my current project being Tokyo 2020 Games.

I began cycling gradually nearly 20 years ago when living in the New Forest. A friend lent me a road bike and took me for a ride. I didn’t take to it initially as it hurt my head when I went over the cattle-grids. When I moved to London I joined a triathlon club and found myself entering increasingly longer races. I did my first Ironman, Sherborne, in 2008, followed by Bolton in 2009 and then Outlaw in Nottingham in 2010. In 2010 I also did my first multi-stage cycling event, the Deloitte Ride Across Britain (1000 miles from John O’Groats to Lands End).

Alongside other cycling adventures, including the Fred Whitton (a gnarly cycle over the hills in the Lake District), the Marmotte and regular commuting to work on my Brompton, I’ve run the Race to the Stones (100km run) and completed the Scilly Isles Swim (16km swimming and 10km walk).

Why TCR 2019?

I was regularly going to adventure talks in London and decided I needed to stop listening to other people talk about adventures and go on one myself. In 2015 I attended an event at the Rapha store where Emily Chappell was facilitating a panel discussion on women in endurance cycling (the speakers had ridden the Race Across America, the Transcontinental and Trans Atlantic Way). I caught Emily on the way out to say thanks, mentioning the Ride Across Britain that we’d both ridden, and she asked me which of the events I’d heard about that evening I’d be keen to do. For want of an answer I said TCR. I can’t remember what drew me to it but I like the idea of not relying on others (which ruled out RAAM) and TCR seemed more of a challenge than TAW. Shortly after, the application process opened for TCRNo5 in 2017 and inquisitively I had a look. The online application process was fun to complete - parts were like a Geography GCSE paper - and without too much thought I filled it in and hit submit.

My 2017 race ended after 2,500 miles at Checkpoint 3 in the High Tatras in Slovakia. Two days before arriving I was mentally finished, riding towards the mountains in the distance but not finding a reason to keep pedalling towards them. At the checkpoint I contemplated my options for an hour or two, but then went into ops mode for getting home; booking a flight, looking at train times etc. As soon as I got on the train I felt I’d made the wrong decision.

The desire to finish the TCR was the underlying reason for entering in 2019, but I also was excited by the route – east to west (coming home) and through France. It fulfilled a romantic desire I’ve long harboured to cycle through France.

What is the Transcontinental Race like?

The fact that the TCR is a race at all, rather than a ride, is an important dimension of the event. It adds a level of excitement and an element of risk. The spirit of the race is what makes it the TCR. People ride it because they buy into the values which are core to the race’s DNA. The rules, whilst simple, aren’t all black and white and the grey space means that over the 4000km of their route riders are constantly making judgements.

Whilst the TCR is a self-supported race the sense of community is a defining feature and interactions with other riders and people on the journey are high on my list of highlights. I instinctively cared for the wellbeing of other riders, though it was nice to be released from the natural sense of obligation to help someone with a puncture or bike issue (which is against the rules) and conversely not feeling guilty that someone was sacrificing their race to help me.

The sheer distance and physical, mental, logistical and emotional challenges test people in a way that most sports events can’t. Since the race format is relatively new, I think we’ve yet to find what makes the ideal TCR rider. In its current state of maturity, this means people like me can be very much part of the race and it’s fun to be part of the evolution.

Having done TCRNo5 I had an idea of what to expect, but over 4000km, nine countries, 16 days and nights there is so much more you don’t and can’t know. I was a moving part in a constantly changing landscape and responding in the way that felt right at the time while also trying to force a pre-defined plan onto the unfamiliar environment.

What sort of Training did you do for TCRNo7?

Physical training - Not much. My Garmin history suggests I rode 400km in 2019 prior to the race (150km in May and 250km in June). I assume this excludes my regular 25km round trip to work and is mostly a 100km lap of the Isle of Wight and a few laps of Richmond Park. I had done quite a lot of running, however, around 1300km over the same six-month period.

I didn’t do anything in terms of nutrition and conditioning. I had been struggling with low iron levels so tried to boost this with red meat, orange juice and less caffeine. On the plus side, I did focus on getting enough sleep, so I went into the race relatively well rested. This was a big confidence boost and a lesson I learned on TCRNo5.

And Planning and Preparation?

There is a huge amount of prep and planning that can be done, but at some point you reach a level of diminishing returns. Eventually you need to get comfortable with the sense you’ll never be ready.

I was ill-prepared for TCRNo5 and took comfort for TCRNo7 in knowing that I couldn’t be less prepared. I’m a big advocate of doing things better second time around and even without huge amounts of additional preparation in 2019 I was mentally in a much more positive place.

My kit and equipment were quite similar to what I’d used in 2017 but with a few upgrades borrowed from friends (e.g. lighter aerobars, a proper handlebar bag vs my 2017 DIY drybag effort). My bike was the same (a £300 Genesis bought on gumtree) as were my shoes, garmin, sleeping kit etc.

My route planning was ‘light touch’. Half a day on Komoot to get the outline route and another half day checking and tweaking. I spent half the plane ride to Burgas checking the end of one section connected with the start of the next and plotting my rough daily schedule. I wouldn’t advocate this approach and suffered particularly in the latter stages with endless ups and downs on country lanes and unnecessary battles through French windfarms which I could have avoided.

What strategies did you have during the event? How well did they work?

Riding rhythm - I started with a daily plan to ride 4 hours on, 15 mins off, 4 hours on, ½ hr off, 4 hours on, 15 mins off, 4 hours on, then sleep (i.e. 16hrs’ riding a day). This lasted for 2 days and whilst short term, was good to have a routine to get me started. After that my routine became unstructured. Limiting faffing was a regular battle and I’d like to have managed this better, if only by moving unconstructive thinking to when I was riding. Easy in hindsight but I could have clawed back numerous hours by cutting out the ‘just 5 more minutes’.

Food – finding food was never an issue to the point where it became a worry. It took me until about day four to have a proper meal (i.e. not garage/grocery store food) and I didn’t do this regularly enough, as mentally and physically I was so much stronger after a proper meal. I ate a lot of nectarines, ice lollies, pain au chocolat, cheese, biscuits and nuts. Oddly, for the first two days I found it a struggle to eat (I had a dry mouth and no appetite), so I had to almost force down food with slugs of water. Towards the end this wasn’t an issue and I ate better and more. When I returned home after the race I was almost gluttonous for the next 3 months, eating two of every meal.

Drink – I did become a bit obsessed with having enough water. Rarely was it actually an issue, but I filled up whenever I had the opportunity.

Sleep – I had planned on a combination of sleeping in hotels and outside, aiming to be in a hotel every three nights, to charge my electronics, wash, rest better etc, and this was roughly what I did. I spent five nights in hotels (albeit one was a sauna), three in a bus shelter (my preferred arrangement), eight in the elements (none of these were very good). There’s a balance between the time saved by sleeping outside vs the comfort and recovery in a hotel room. Typically, I got between 4 and 5 hours of sleep a night; falling asleep instantly but often having broken sleep as my legs seemed to keep turning.

Power – Getting power for charging was probably my biggest ongoing worry. I didn’t have a dynamo and was reliant on power packs. The impact was time wasted in garages etc. trying to charge devices and losing the capacity to take photos when my phone didn’t have charge. In hindsight I should have prepared better in this area, having a dynamo option for the essentials (lights, gps) and ensuring I had effective power packs/cables etc for use on the continent.

How did the race go for you?

For all the challenges (see below), excitements and dramas I LOVED the race. I got to the finish and felt a wonderful sense of inner calm and achievement. I missed the GC cut off by about eight hours and, 6 months on, this bothers me a bit more than it did at the time, but it’s a small downer compare to my overall feelings of total enjoyment from the race and I wouldn’t swap any of the experience for a few extra hours back. I look back at every day, each interaction, each leg-sapping climb and each rain-soaked day with a general sense of happiness and fondness. It certainly wasn’t always fun, but I never felt that sense of ‘can’t find reason to continue’ that I felt prior to scratching TCRNo5.

What were the most challenging moments?

Because I didn’t ever feel hopelessly low or the worry about scratching, coping felt so much easier. I had a sense of managing a physical/logistical response vs the mental battle. There were some challenges though, for sure.

Physical Challenge No 1 – saddle sores from day three. Without going into detail, they were raw and agony for the ENTIRE ride and a daily challenge to manage seat position, padding, hygiene etc. It was partly my fault, for using a new untested seat (which I thought couldn’t be worse than the one that gave me saddle sores on TCRNo5), but combined with heat, rain, long days on the bike, it was horrible.

Physical Challenge No 2 – I cartwheeled off my bike when I misjudged a curb going onto a cycle path, and landed on a rocky path: blood was pouring from both knees and my right arm and I broke my nose. Wonderful and kind people offered help; a lift to hospital etc but, knowing that if I went to hospital my race would be over (no doctor would encourage me to continue), I did the British ‘I’m fine’ thing, and got back on my bike gingerly to demonstrate. To some extent I was fine, I knew I hadn’t broken any bones that would stop me riding, but I was in a fair amount of pain, and more so as the adrenalin wore off. I had a nice moment a few days later when arriving at Checkpoint 4. A number of riders and volunteers were congregating at the hotel in Bourg d’Oisin and I started to get sympathy for my injuries. A fellow rider who I’d met at various points came up to me and jabbed his oily dirty thumb into my cheek just below my eye socket. Initially this seemed odd, but reassuring once he mentioned he was a facial surgeon and my broken nose wouldn’t cause lasting damage.

Mechanical Challenge – waking up at Checkpoint 3 to a volunteer asking ‘is this bike yours?’, while shaking the back wheel from side to side. Yes mine, and no, I’d no idea how to fix it. I got to a sport shop 50km away, and after initial resistance the mechanics were fantastic - TCR bike chat can pull interest and favours. An hour later, I was on the road with the bike purring better than when I started the ride. Unfortunately, later that day was when I crashed, which knackered the gearing, which I was more cross about (as I was heading into the Alps) than my broken nose. I had another stroke of luck the next morning: it was pouring with rain and, not having much luck finding a bike shop, I knocked on the window of a white van to ask the driver if there was a bike shop in the village. He directed me down a forest track where I came to a workshop (like something out of a 60s film with motorbikes and parts everywhere). The mechanic (aged c.70+) was dodging the rain and getting into his van but with my broken German I managed to convince him to look at my gears. Fifteen minutes later he had my bike fixed. And in the process hadn’t once taken the lit cigarette out of his mouth. Beyond these two mechanicals, I had no problems with my bike and not one puncture over the 4000km.

Scared – cycling through an industrial area in the back streets of Sofia I had my ‘dog experience’. It’s almost a rite of passage, but not one you can prepare for and my biggest fear before the race. It was late (c.midnight) and I wanted to get most of the way round Sofia before sleeping. I passed an industrial building and two big, angry, snarling dogs came out and started chasing me; one on either side of my back wheel. Then I saw another dog about 50m ahead, streaking in from the left to join the attack. For all the advice – bells, water, sticks, stones, and my favourite; “getting off and putting your bike between you and the dog!”, I couldn’t do anything except pedal like a cartoon character and scream ‘please go away’. They gave up when a car came the other way and they lost interest in the ‘game’, but for two minutes I experienced a parallel sense of total fear and total adrenaline.

And the best moment?

There are so many; but here are three highlights:

I felt a wonderful sense of bonding with some of the other riders. They came and went as companions over stages of the journey and often a meeting would be a quick hi at a petrol station, but so many of these meetings were highlights of a day and in hindsight are the highlights of my race. Two meetings in particular:

Tom and Adrian – riding as a pair, typically talking the whole time, strong on the flats (when they overtook me), but faffing, aka enjoying the experience, a lot (which is when I overtook them). I met them a few times over the middle sections of the race. One evening, after I’d had a coffee at a questionable bar half way up a hill, I found the perfect bus stop to sleep in. Solid, big, dry, in the middle of nowhere but not eerily so. I got myself ready for a few hours’ kip and just as I was about to lie down, Tom and Adrian showed up, thinking they too had found the perfect bus shelter... They weren’t going to stay - I truly meant my offer of sharing, the bus-stop, but it really wasn’t big enough for three - but for a few minutes we shared daft stories and it was like I’d invited friends to mine for a catch up.

Lucie and Jimmy – I loved it when one of these two rode past. They weren’t a pair, but two or three times they happened to be together as we passed one another and I could sense them coming. They bought an air of fun and laughter and made riding seem easier. The morning of my birthday I woke early and rode hard for four hours to get through Lyon before the morning traffic. Having sacrificed breakfast to make it out the other side of the city, I was ready to find food by about 0900. And pedalling alone on a random quiet road, who should I bump into but Lucie and Jimmy? Such a treat and I was smiling and laughing in an instant. Jimmy’s laughter was punctuated by getting a puncture, so Lucie and I rode into a little town with a wonderful bakery and coffee shop. I learned from Lucie that it was quite acceptable to buy five croissants in one sitting (and eat three of them immediately) and we sat happily in the sun eating breakfast and raising a coffee to my birthday.

Galibier – The good moment was the joy of the climb relative to how I thought it was going to be, particularly as I sat at the bottom with nothing in the tank. After a day of heavy rain, busy roads and scaling the Col de Telegraph, I couldn’t fathom how I’d possibly get up it. And it didn’t start well – as I was descending into the town at the bottom of the climb, I drifted to a sleep on my bike and careered across onto the wrong side of the road. Luckily the oncoming car was going slowly but it shook me into getting off the bike taking a power nap.

I still don’t quite know where the mojo came from, but it’s a simple fact of realising you don’t have an option better than getting on the bike and pedalling. As I set off a host of factors made me think luck was on my side. I counted six positives: my bike was purring (not bad after my crash two days before); the climb turned out to be only 20km (I’d misread a sign and thought it was 36km); climbing took pressure off my saddle sores; I found somewhere to get a coffee and ice cream after I thought I’d passed the last refuel point; it was undoubtedly a beautiful climb and the gradient wasn’t as steep I thought it would be (max 10% as opposed to the 15-20% I was expecting in places).

The Finish - The ending of my journey was almost perfect. Brest isn’t beautiful by most people’s admission, but as I rounded the final bay I started to feel emotional. I’m not great with my emotions – I cry without reason - and for the first time in the race I felt myself well up. I didn’t want to ride into the welcome of riders at the finish crying so I stopped myself before the finish came into view. And then it did come into view and it was wonderfully underwhelming. No fanfare, no banners, no cheering crowd. Just 5 riders who’d hung around Brest and a lot of grey. Brest may not be beautiful, but this finish was.

The TCR is understated. It’s not about the finish, it’s about the personal journey, and the quiet ending bought this to home. I had a beer, and then a second. An hour later I was back on the bike, heading to Brest station for the journey home.